groundhog biology and ecology

on this page

taxonomy and morphology

what groundhogs are

groundhogs (marmota monax) are basically giant ground squirrels:

- order: rodentia

- family: sciuridae (squirrel family, 285 species)1

- genus: marmota (15 marmot species worldwide)1

- species: monax (means “solitary” - they live alone)2

several subspecies exist. in michigan, we have marmota monax rufescens.3

built for digging

everything about groundhogs is optimized for underground life:

teeth

- incisors never stop growing (wear down from constant gnawing)

- white or ivory colored (most rodents have yellow/orange teeth)4

- strong enough to gnaw through roots while digging

digging equipment

- front feet: 4 toes with curved claws like mini excavators

- hind feet: 5 toes for stability

- incredibly powerful front legs1

surveillance features

eyes, ears, and nose sit high on their flat heads - perfect for peeking out of burrows with minimal exposure5

scent communication

groundhogs mark territory with multiple scent glands:

males mark more during breeding season - you’ll smell it near burrow entrances.6

note - if you plan to eat groundhogs, the most important thing to do is find and remove the scent glands without damaging them, especially if you harvest them during the breeding season. if you fail to remove them, or if they are shot, crushed, or cut, you will have a very disappointing stew by the time you’re done.

habitat distribution

geographic range

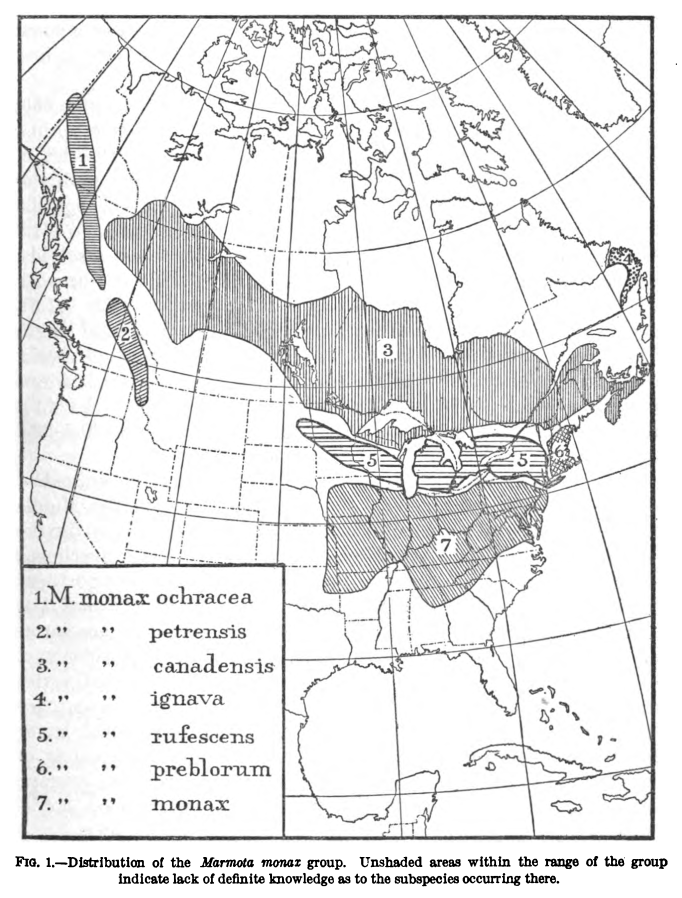

groundhog distribution across north america - michigan sits well within their core range

groundhog distribution across north america - michigan sits well within their core range

groundhogs are found throughout the eastern united states and canada, with michigan sitting squarely in their primary range. they’re absent from the far north and most of the western united states.

how we created a groundhog paradise

before settlement, groundhogs were limited by the natural distribution of clearings with suitable soil types. in the midwest, there really wasn’t much of that, as mature trees tended to dominate those areas and rob the groundhog of accessible food. then, we changed everything…

seasonal habitat shifts

| season | where they go | why |

|---|---|---|

| winter | woods, brushy slopes | better insulation, tree roots protect burrows |

| spring/summer | open fields, pastures | close to food |

| fall | crop field edges | maximum feeding efficiency |

urban vs rural groundhogs

illinois research shows remarkable adaptation:7

| what changes | rural groundhogs | urban groundhogs | difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| territory size | baseline | 10% of rural | 10x smaller |

| number of burrows | more | fewer | concentrated |

| burrow spacing | spread out | close together | higher density possible |

burrow architecture

underground engineering

groundhog burrows are seroius feats of excavation:

- length: 8-66 feet of tunnels

- depth: up to 5-6 feet underground

- dirt moved: 275-700 lbs per burrow8

built-in flood prevention

that upward bend after the entrance? it’s a water trap that keeps the living areas dry, kind of like proper human plumbing.5

entrance types

main entrance

- huge dirt mound (the “porch”)

- doubles as lookout post (or spawn camping spot if you’re hunting)

- you can’t miss it9

plunge holes (back doors)

- 1-5 hidden exits per burrow

- dug from inside out

- no dirt pile - nearly invisible

- emergency escapes10

underground rooms

they’re surprisingly clean - when a bathroom chamber fills up, they seal it off and dig a new one.5

seasonal den strategy

winter burrows

- where: woods, under tree roots or stone walls

- design: single entrance they plug from inside

- why: maximum insulation and safety during hibernation9

summer burrows

- where: open fields near gardens and crops

- design: multiple entrances for quick escapes

- why: short commute to food9

what they eat

appetite

an adult groundhog eats over a pound of plants daily.10

food preferences

personally, i’ve only ever seen a groundhog eat an egg once, when a raccoon set ended up with a very unexpected visitor, but i can confirm that they will actually eat eggs when curious or desperate.

seasonal diet changes

| season | what they eat | why |

|---|---|---|

| early spring | dandelions, coltsfoot | desperately hungry after hibernation |

| summer | variety of greens | picky eaters, choosing high-protein plants |

| late summer/fall | everything green | hyperphagia - storing fat for winter |

water needs

groundhogs almost never drink from streams or ponds. instead:11

- get water from juicy plants

- feed at dawn/dusk when plants are dewy

- won’t eat dry or wilted vegetation

population dynamics

breeding facts

| aspect | details |

|---|---|

| mating system | males breed with multiple females |

| litters per year | just one |

| babies per litter | 2-6 (usually 4-5) |

| breeding age | 2 years (sometimes 1) |

| lifespan | average 3 years, max 6 |

what kills them

main causes of death:

- predators (coyotes, foxes, bobcats, hawks)

- cars (especially young ones in july)

- disease and parasites

- starvation (not enough fat for winter)

ecological role

benefits (yes, there are some)

i’m only begrudingly listing these for the sake of completeness. despite the damage they cause:

- their digging aerates soil (just never where you want it)

- they’re food for predators (so maybe the hawk will kill fewer chickens)

- abandoned burrows shelter 25+ other species (that you also don’t want…)

- they’ve uncovered archaeological sites12 (i’ll take indy, thank you)

who moves into old burrows

communication

sounds they make

| sound | when they use it | what it means |

|---|---|---|

| sharp whistle | danger spotted | warning call (hence “whistlepig”)13 |

| teeth chattering | confrontation | back off |

| hisses, growls | cornered | leave me alone |

| squeals | hurt or terrified | distress |

body language

- standing up tall to scan for danger

- tail waving when alarmed

- puffing up during fights

why they’re so successful

groundhogs thrive in our landscapes because:

- they eat almost any green plant

- they love the edges we create everywhere

- their burrows are engineering marvels

- they time babies perfectly with spring growth

- they adapt to suburbs as easily as farms

references

[1] Nowak, R.M. (1999). Walker’s Mammals of the World (6th ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

[2] Kwiecinski, G.G. (1998). Marmota monax. Mammalian Species, 591, 1-8.

[3] Baker, R.H. (1983). Michigan Mammals. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

[5] Svendsen, G.E. (1976). Structure and location of burrows of yellow-bellied marmots. Southwestern Naturalist, 20, 487-494.

[6] Meier, P.T. (1992). Social organization of woodchucks. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 31, 393-400.

[8] Grizzell, R.A. (1955). A study of the southern woodchuck, Marmota monax monax. American Midland Naturalist, 53, 257-293.

[9] Michigan United Conservation Clubs. (2023). Hunting for a Shadow: Groundhogs. Lansing, MI: MUCC.

[11] Hamilton, W.J. (1934). The life history of the rufescent woodchuck. Annals of Carnegie Museum, 23, 85-178.

[12] Groundhog as Archaeologist. Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

[13] Schwartz, C.W., & Schwartz, E.R. (2001). The Wild Mammals of Missouri. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

the same adaptations that make groundhogs successful make them problematic. knowing how they work helps manage them better.